AI, Code and the Monkey Selfie

By John Hardy

Writing into being.

By John Hardy

An Elephant in the Room Too Large to See

Software engineers are experiencing massive disruption right now. We're all being told to adopt AI coding tools for productivity gains that are genuinely remarkable. But there's something nobody in our industry is talking about.

The US Copyright Office has recently advised that AI-generated code that lacks sufficient human creative authorship isn't copyrightable.

It's public domain.

What does "lacking sufficient authorship" mean? It means prompting the AI isn't authorship. Neither is specifying requirements, guiding the output, testing it, or validating it.

These activities focus on what to make, not on how it's made. They're about the requirements, not the creative expression. The actual code, the creative expression, comes entirely from the AI which means the software being shipped by companies racing toward AI-driven development may not be legally ownable.

Engineers need to understand this, because it fundamentally changes what we're actually building and why. Companies are chasing productivity and cost savings without reckoning with a fundamental legal problem: they may not own the output. This isn't a complaint about disruption, it's a flag about an elephant in the room that's so big nobody's even noticed it yet!

Does your company know that the software that they are paying so much money to Microsoft, Anthropic and OpenAI to develop is probably not copyrightable and is therefore in the public domain?

No human author. No copyright claim.

There’s an interesting legal question emerging around AI-generated software that reminds me of the famous “monkey selfie” case.

In that case, a photographer owned the camera, set up the conditions, and facilitated the shot but because the monkey actually pressed the shutter, the courts found there was no human author. No human author meant no copyright. And no copyright meant the image effectively fell into the public domain: i.e. nobody could assert any ownership over it.

Now consider large-language-model generated code.

If a developer simply prompts an AI system to produce a loan calculator (or any other software) and ships the result with minimal human authorship over the actual expression of the code, the situation starts to look structurally similar. The U.S. Copyright Office has already taken the position that works generated without “traditional human authorship” are NOT eligible for copyright protection. That doesn’t automatically resolve every case, but it establishes an important default assumption.

If that default holds, the implications are significant:

• Purely AI-generated code may not be copyrightable.

• If it is not copyrightable, IT CANNOT BE OWNED.

• If it cannot be owned, it cannot be licensed in the conventional sense.

That affects not only commercial licensing, but also open source licensing. Licences such as the GNU public license depend entirely on copyright to enforce their terms. Without copyright, the legal mechanism behind “copyleft” weakens or disappears for the AI-generated portions.

This does not mean all AI-assisted software is public domain. Where humans meaningfully design, edit, select, or structure the work, copyright may still attach to those contributions. But the boundary between “tool-assisted authorship” and “machine-generated output” remains largely untested in courts.

We are entering a period where the legal status of software, something the industry has treated as settled for decades, may need to be reconsidered.

If large volumes of production code end up legally uncopyrightable by default, the consequences for ownership, licensing models, and open source ecosystems could be profound.

This space is still evolving, and the unanswered questions are arguably as important as the answers.

By John Hardy

In January 2025, the US Copyright Office concluded its review of AI-generated content with a finding that every software developer should read carefully. Code produced through conversational prompting of a large language model has no legal author. The human who typed the prompts is not, in the eyes of the law, the creator of the output. The work lands in the public domain by default, unprotectable by any open source or commercial licence. No GPL. No MIT. No proprietary rights of any kind. The code cannot be owned.

That advice arrived just as vibe coding was becoming the default mode of AI-assisted development. The term, coined by researcher Andrej Karpathy early in 2025, describes a workflow most developers now recognise: you describe what you want in a chat window, the model returns code, you iterate on the result, and you ship it. The process is fast and feels productive. What it does not do, per the Copyright Office's January 2025 advice, is produce software that anyone legally owns.

The reason is structural, not incidental. When a programmer describes what they want to an LLM in a chat window, they are modulating an autonomous system rather than controlling a deterministic one. The model makes its own creative decisions about how to fulfil the request. Those decisions, not the programmer's description of them, are what give the code its particular shape. The Copyright Office is measuring the distance between intent and output: when that distance passes through a black box that makes independent creative choices, the human's authorial claim does not survive the crossing.

This piece works through what that means for the software industry, and what a different interaction model would need to look like to restore the authorial chain that vibe coding breaks.

"Vibe coding" is Karpathy's term, and the name fits the practice. You type something like "write me a function that parses CSV files with embedded commas" into a chat window, and the model returns code. You paste it in, run it, find a problem, paste the error back. You iterate. Eventually the code works. You ship it.

What you did in that process was modulate an autonomous system. The LLM is a probabilistic state machine with its own internal logic, its own weights, its own way of resolving ambiguity. When you type a prompt, you are adjusting the environment around that machine. The connection between your instruction and the output passes through a black box you cannot inspect or direct. The creative decisions embedded in the code were made by the model, not by you: the choice of data structures, the error handling strategy, the tradeoffs in the implementation.

That gap is what the Copyright Office is measuring. Authorial content requires a direct chain from human creative intent to the finished work. Prompting breaks that chain.

Compare this with a compiler.

When I write C, I am making specific choices at every level: the types I declare, the function signatures, the control flow, the memory management decisions. The compiler translates that into binary deterministically. A specific input always produces a specific output. The binary contains no creative decisions that were not already in my source. It is a mechanical translation of my intent. The compiled programme is mine.

A text editor works the same way. When I select a region and apply a transformation, the editor does exactly what I asked. The result reflects my choices, not the editor’s. These tools are transparent mediators. They carry authorial intent through to the output intact.

A chat-window LLM is not a transparent mediator. It is an autonomous creative system that takes suggestions and produces its own work in response to them. This distinction matters legally and practically.

The sculptor analogy makes the contrast concrete.

A sculptor working in clay is in direct contact with the medium. Every decision is immediate: where the thumb presses, how much material is removed, what the surface texture becomes. The clay has properties that resist and suggest, but every shape it takes is the result of direct physical manipulation. The finished work is the sculptor’s because their creative choices are embedded in every cubic centimetre of it.

A patron who describes a sculpture to a skilled artisan and reviews the result is doing something different. The description might be detailed. The patron might give corrections over several rounds. The final object might match their vision closely. But the creative decisions that went into the making, the moment-by-moment choices about form and surface, belong to the artisan. The patron commissioned the work. They did not make it.

Vibe coding is patron work. The LLM is the artisan. The Copyright Office's advice reflects this accurately.

The implication for the software industry is large.

Development is moving fast toward vibe-coded workflows. The AI companies are pushing this direction with intent: faster adoption, more usage, more dependence. But every line of vibe-coded software is, per the Copyright Office's advice, public domain on delivery. It cannot be protected by GPL, BSD, MIT, or any open source licence. It cannot be protected by commercial copyright. A company that ships a product built through vibe coding has nothing to licence and nothing to sell. An open source project that accepts vibe-coded contributions cannot meaningfully extend its licence terms to cover those contributions.

Open source licensing depends entirely on the assumption that code has an author whose rights are transferable. If the underlying code cannot be owned, the licence terms have nothing to attach to. Copyleft dies first, because copyleft is a mechanism for asserting ownership strategically. Commercial licence dies alongside it.

This might read as a theoretical problem at present. The structural consequence arrives when the volume of vibe-coded software grows large enough to dominate a codebase. At that point, the codebase’s legal status becomes genuinely uncertain, and so does everything that depends on it.

The alternative is to change the interaction model.

If prompting is modulation, the solution is to build tools that put the programmer in direct contact with the medium. The goal is a feedback loop tight enough that the programmer’s choices are embedded in the output at every stage, not merely described to an autonomous system and handed back as a result.

This looks less like a chat window and more like an editor. The programmer defines structure: the shape of a module, the contract a function must satisfy, the types that flow through a system. The model expands that structure deterministically, filling in the mechanical consequence of choices the programmer has already made explicitly. When the programmer changes a constraint, the model recalculates. They are not asking; they are shaping. The medium responds to pressure the way clay does: immediately, locally, without independent agenda.

The word that carries the legal weight here is deterministic. A given specification, in a given context, produces the same output every time. This is what makes the output a derivative of the programmer’s choices rather than an autonomous creation. Temperature zero. No probabilistic creative leaps. Mechanical translation of explicit intent into working code.

This is what compilers have always done. The innovation is applying the same principle to a higher-level specification language, one expressive enough to capture design intent while remaining precise enough to drive consistent output.

The choice the industry faces now is real. The path being actively marketed, faster outputs, more automation, less friction, leads to a world where programmers are patrons and the software they commission belongs to no one. The Copyright Office's advice is not a warning about a possible future. It describes the present.

The sculptor metaphor captures what needs to change. Direct contact with the medium. Choices embedded in the work at every stage. A feedback loop tight enough that the output is a derivative of specific human decisions rather than the autonomous product of a system that was merely pointed in a direction.

That kind of tool is not built yet in the form the problem requires. The chat window is. The vibe coding workflow is. The question is whether the industry builds the alternative before the assumption that software has no author becomes too embedded to examine.

By John Hardy

ZAX matters most when a Z80 program stops being a single routine and starts becoming a codebase. At that point the problem is not instruction syntax. The problem is keeping modules, memory layouts, call boundaries, and control flow understandable as the program grows. ZAX gives those parts a clear place in the language so the source continues to read like a program instead of a pile of local assembler conventions.

ZAX starts by treating the source file as a module. Imports live at module scope. Code and data live in named sections. Public entry points are marked with export. External routines at fixed addresses can be declared once and then called through a normal function-like surface. This gives a project a stable shape from the first screenful of source onward.

That structure is useful because it reduces hidden knowledge. I do not need to remember which label is intended as an entry point or which block of bytes belongs to which subsystem. The file tells me.

The next improvement comes from typed layout declarations. ZAX supports arrays, records, unions, and enums so the source can describe memory the same way the program uses it. The compiler then handles the offset arithmetic that would otherwise live in comments or hard-coded constants.

That changes the way addressing reads. A form like sprites[C].x expresses the same intent that exists in my head when I write the code. The addressing model still lowers to ordinary Z80 work, but the layout calculation moves into the compiler where it belongs. The result is less drift between the program design and the addresses in the source.

ZAX also gives functions a real boundary. A function declaration names the arguments, return type, and locals. An external ROM or BIOS routine can be declared with the same surface, including its fixed address. Call sites then stay compact and readable while the compiler handles the push, call, and cleanup sequence consistently.

That consistency matters in assembly. A large program collects many tiny calling conventions if the tool does not provide one. ZAX gives the project a single calling model that I can rely on across modules.

Structured control flow completes the picture. ZAX provides if, while, repeat, and select, and each one still depends on the flags that the instructions have already set. The source gains the shape of a loop or branch without losing the underlying machine logic.

This kind of loop is typical:

ld b, MsgLen

repeat

ld hl, p

ld a, (hl)

inc hl

ld p, hl

push bc

bios_putc A

pop bc

dec b

until ZThe machine story is still there. dec b sets the zero flag and until Z uses it. ZAX simply carries the branch bookkeeping so the source keeps its shape.

ZAX does not try to hide the hard parts of assembly programming. It gives those hard parts a better environment. Source files gain a module structure. Layouts stay attached to the code that uses them. Calls follow a single convention. Control flow reads cleanly. That is enough to make a large difference in a long-lived Z80 project.

That is the practical promise of ZAX. It keeps assembly direct and makes bigger programs easier to hold in my head.

By John Hardy

One of the most distinctive parts of ZAX is op, a way to define new instruction-shaped building blocks with typed operands. I wanted this because reusable patterns appear constantly in assembly work, especially on the Z80, and traditional macro systems do a poor job of carrying those patterns once a project becomes large. ZAX keeps the convenience of reusable instruction families while grounding them in the actual operands that appear at the call site.

An op looks and reads like an instruction. It expands inline, so there is no call overhead, and it can be overloaded so a single name covers a family of related operand shapes. That makes it useful for the repetitive low-level work that assemblers have always needed macros for.

This is a small example:

op add16(dst: HL, src: reg16)

add hl, src

end

op add16(dst: DE, src: reg16)

ex de, hl

add hl, src

ex de, hl

endAt the call site, add16 DE, BC reads like a normal instruction. The compiler sees that the destination is DE, selects the matching form, substitutes the operands, and emits the correct inline sequence. The source stays compact and the machine behaviour stays visible.

The important idea is that operands are matched by kind. A declaration can require HL, any reg16, an immediate, a condition code, or another specific operand class. That gives reusable patterns clear boundaries. If I pass the wrong shape, the compiler can reject the call in terms that make sense for the original source.

This is a practical improvement over text substitution. The tool understands that DE is a register pair and Z is a condition code. It is working with the parsed program rather than a stream of pasted tokens. That keeps reusable instruction forms connected to the machine concepts they represent.

Typed ops matter because they let an assembler project grow without pushing more logic into fragile macro text. I can give a repeated pattern a name, define the valid operand forms once, and keep the final expansion inline and inspectable. That is exactly the kind of facility a structured assembler should offer.

ZAX uses typed ops because they are a better unit of reuse for assembly code. They keep the language close to the machine while giving repeated instruction patterns a clear and durable home.

by John Hardy

ZAX is a structured assembler for the Z80 family. I built it for the stage of assembly programming where a project stops being a few routines and starts becoming a codebase. Registers, flags, memory placement, and instruction choice still matter just as much as they do in ordinary assembly. ZAX keeps those decisions explicit and adds structure around them so the source stays readable as the program grows.

The goal is practical. I want the directness of assembly without letting larger programs dissolve into labels, calling conventions in comments, and hand-maintained offset arithmetic. ZAX gives that work a place in the language itself.

ZAX still works in assembly terms. I choose registers. I set flags with ordinary Z80 instructions. I decide what lives in ROM and what lives in RAM. A call still lowers to a normal Z80 call sequence. A loop still depends on the machine state I established in the instructions above it.

That directness is important because the machine is the whole point. When I read a ZAX file, I still want to see how the code relates to hardware, registers, flags, and storage. ZAX keeps that view intact.

What ZAX adds is structure at the level where larger projects usually become fragile. Source files become modules with imports, named sections, and exported entry points. Memory layouts can be declared with arrays, records, unions, and enums. Functions have typed arguments, locals, and a stable calling convention. Control flow can be written with if, while, repeat, and select, while still using the Z80 condition codes directly.

This gives the source a stronger shape without changing what kind of program it is. It is still assembly. It simply carries more of the design in the file itself.

Here is a small example from the kind of code ZAX is meant to support:

const MsgLen = 5

section data vars at $4000

msg: byte[5] = "HELLO"

end

extern func bios_putc(ch: byte): void at $F003

export func main(): void

var

p: addr

end

ld hl, msg

ld p, hl

ld b, MsgLen

repeat

ld hl, p

ld a, (hl)

inc hl

ld p, hl

push bc

bios_putc A

pop bc

dec b

until Z

endThe instructions are ordinary Z80 work. The file around them is the part that changes. Data has a named section. The external BIOS routine has a declaration. The program entry point is explicit. The loop reads as a loop.

The value in ZAX is that assembly projects keep their shape for longer. Imports show where names come from. Layout declarations keep offsets attached to the data they describe. Function boundaries give calls a stable form. Structured control flow makes the execution path easier to recover after time away from the code.

That is the concept behind the project. ZAX is assembly with enough structure to stay coherent when the program becomes real.

Written by John Hardy on February 7th, 2026

The TEC-1G includes support for the ST7920 graphical LCD controller, a chip that drives 128×64 pixel displays using a parallel interface. Programs can write pixels to display buffer memory and read them back for verification or manipulation. The read path has a quirk that tripped me up: the first read after setting an address returns the data from the previous address, not the address you just specified.

I discovered this while testing a graphics routine that drew shapes and then verified the framebuffer contents. The routine worked correctly on real hardware but failed in my emulator. The verification loop expected specific pixel patterns and found zeros instead. The writes were landing correctly (I could see the display updating) but the reads returned wrong values.

The ST7920's data sheet explains the read pipeline in a few terse sentences. When you set the address counter with a command, the controller latches the new address but does not immediately fetch the corresponding data. The data bus still holds the previously fetched value. To read the data at the new address, you must perform a dummy read that primes the pipeline, then perform the actual read that returns the wanted value.

The correct read sequence proceeds through four steps. First, write a command to set the address counter to address N. Second, perform a dummy read and discard the result. Third, perform the real read which returns data at address N. Fourth, subsequent reads return data at incrementing addresses starting from N+1 as the address auto-increments.

The dummy read triggers an internal fetch from address N. That fetch completes during the read cycle, and the data becomes available for the next read. If you skip the dummy read, you get stale data from whatever address was previously active.

A naive emulator models the data read as a simple array lookup: given address N, return memory[N]. This works for writes, which take effect immediately, but fails for reads because it ignores the pipeline delay. The real chip does not deliver data from address N until one read cycle after you request it.

My initial implementation did exactly this: the read handler received the address and returned the corresponding byte from the display buffer. Writes worked as I expected them to work. Single reads without address changes also worked correctly. Yet any code that set an address then immediately read from it returned the wrong value.

The fix required modelling the pipeline state. The emulator now tracks two values: the current address counter and the pending read value. When code sets a new address, the pending value stays stale. The first read returns the pending value and then loads the new address into the pipeline. Subsequent reads continue through the buffer with automatic incrementing.

The TEC-1G runtime maintains a glcdPendingRead field alongside the display buffer. When the address counter changes, this field is not updated. When a read occurs, the emulator returns glcdPendingRead and then fetches the byte at the current address into glcdPendingRead for the next read. The address counter increments after the fetch.

readGlcdData(): number {

const value = this.glcdPendingRead;

this.glcdPendingRead = this.glcdBuffer[this.glcdAddress];

this.glcdAddress = (this.glcdAddress + 1) & 0x1FFF;

return value;

}Setting a new address resets the pipeline state to a known value. I chose zero, which matches what I observed on hardware when reading from an uninitialised region.

setGlcdAddress(address: number): void {

this.glcdAddress = address & 0x1FFF;

this.glcdPendingRead = 0x00;

}The dummy read that programs must perform consumes the zero then primes the pipeline with the actual data at the new address. Subsequent reads then return correct values from the buffer.

I wrote a test that exercises the pipeline behaviour explicitly:

it('returns stale data on first read after address change', () => {

runtime.writeGlcdData(0xAA); // Write 0xAA at address 0

runtime.setGlcdAddress(0); // Reset address to 0

const dummy = runtime.readGlcdData(); // Dummy read

const actual = runtime.readGlcdData(); // Real read

expect(dummy).toBe(0x00); // Stale/reset value

expect(actual).toBe(0xAA); // Actual data

});The test captures the exact behaviour that the original routine depended on. With the pipeline modelled correctly, the verification loop in the graphics routine passes.

I confirmed the behaviour on a physical TEC-1G with an ST7920 display attached. A short Z80 program writes a known pattern to display memory then sets the address then performs reads then reports the values through the serial port. The first read after setting the address returned zero. The second read returned the written value. The emulator now matches the hardware behaviour.

The data sheet describes this behaviour, but the description is easy to overlook. The phrase "dummy read" appears once without much context. I had read the data sheet before and missed the implication. Seeing the actual hardware behaviour made the documentation make sense retroactively.

Peripheral emulation often requires modelling internal timing and sequencing, not just the logical contents of registers. The ST7920's read pipeline is invisible to code that only writes to the display—writes take effect immediately—but becomes critical for code that reads back. An emulator that supports only writes might pass basic tests and fail on more sophisticated programs.

The fix was small, just a few lines of state management. Finding the bug took longer because the symptoms (reads returning zero) could have indicated many different problems. Once I understood the real chip's behaviour, the solution was obvious. The lesson is familiar: when emulation diverges from hardware, the data sheet usually contains the answer, even if it takes a second reading to find it.

By John Hardy

The Z80 has a baroque instruction encoding that requires careful handling. A single-byte opcode might decode to one instruction, or it might be a prefix indicating that the real opcode follows. The CB prefix introduces bit manipulation instructions. The DD and FD prefixes switch the operand register from HL to IX or IY. The ED prefix accesses extended instructions like block moves and I/O loops. Combinations like DD CB introduce indexed bit operations with yet another encoding scheme. Every path through this maze needs code to handle it.

The Debug80 decoder started as a single file with nested switch statements. I added cases as I encountered instructions during testing. By the time I had reasonable Z80 coverage, the file had reached 1,616 lines. The primary opcode switch alone spanned hundreds of lines. The prefix handlers added hundreds more lines of their own. The file had become difficult to navigate and slower to load than I liked.

I reorganised the decoder into separate modules by prefix:

- decode-primary.ts handles unprefixed opcodes (the main instruction set) - decode-cb.ts handles CB-prefixed bit operations - decode-dd.ts handles DD-prefixed IX instructions - decode-fd.ts handles FD-prefixed IY instructions - decode-ed.ts handles ED-prefixed extended instructions - decode-ddcb.ts handles the indexed bit operations (DD CB and FD CB) - decode-helpers.ts contains shared utilities for operand formatting

Each module exports a single decoder function that takes the instruction bytes and returns a decoded result. The main decoder dispatches to the appropriate module based on the first byte. The structure mirrors the CPU's own decoding logic: check the prefix, then delegate.

The split made each module independently testable. I could verify CB instructions without loading the entire decoder. The file sizes dropped to a few hundred lines each, small enough to hold in working memory while editing. The organisation also made gaps visible in the implementation. When I noticed that decode-ed.ts was missing block I/O instructions, the absence stood out.

A debugger decodes instructions constantly. Single-stepping through code means decoding the current instruction, then the next, then the next. Memory views decode ranges of bytes to show disassembly. Breakpoint displays decode the instruction at each breakpoint address. The same instructions decode repeatedly during a debugging session.

The Z80's instruction encoding is deterministic: the byte sequence 21 00 40 always decodes to LD HL, 4000h regardless of context. No mode switching changes the interpretation of bytes. No hidden state affects the decoding process. Once decoded, an instruction's representation remains constant forever. This determinism makes caching straightforward to implement.

JavaScript's WeakMap provides a natural caching mechanism for object keys. I treat each instruction's byte sequence as a Uint8Array and use that array as the cache key. When decoding, the decoder first checks whether the byte sequence exists in the cache. If so, it returns the cached result immediately. If not, it decodes the instruction then stores the result then returns it.

const cache = new WeakMap<Uint8Array, DecodedInstruction>();

function decode(bytes: Uint8Array): DecodedInstruction {

let result = cache.get(bytes);

if (result) {

return result;

}

result = decodeInstruction(bytes);

cache.set(bytes, result);

return result;

}The WeakMap holds references weakly so entries can be garbage-collected. When the byte array goes out of scope elsewhere, the cache entry becomes eligible for garbage collection. This prevents the cache from growing without bound during long debugging sessions. The cache stays proportional to the working set of instructions currently relevant rather than accumulating every instruction ever seen.

I instrumented the decoder during typical debugging sessions to measure cache effectiveness. The hit rate depends on the program under test, but typical values exceed 95 percent. A tight loop like a delay routine might decode the same handful of instructions thousands of times. The decoder does the work once and serves the cached result for subsequent hits.

The miss rate spikes when scrolling through memory views because each scroll brings new addresses into view. Even then, returning to previously viewed regions hits the cache. The steady-state behaviour favours the cache heavily.

The cache lookup is fast—a hash table probe and a reference comparison. The cache miss path runs the full decoder, which involves a switch dispatch and operand parsing. For multi-byte instructions with displacement values or immediate values, the parsing includes bounds checking alongside endianness conversion. The cached path skips all of that.

The memory overhead is proportional to the number of unique instructions in the cache. Each entry holds a Uint8Array key (typically 1 to 4 bytes) and a decoded result object (a few tens of bytes including the mnemonic string and operand descriptions). For a program with a few hundred unique instruction patterns, the cache consumes a few kilobytes. The memory cost is negligible compared to the time saved.

Breaking the decoder into modules forced me to think about the instruction set systematically. The Z80's prefixing scheme, awkward as it sometimes feels, maps naturally onto a module-per-prefix structure. The code now reflects the architecture it decodes.

The caching emerged from profiling the decoder during real sessions. I noticed redundant decoding in the hot path and asked whether the work was necessary. The deterministic encoding made the answer obvious while the WeakMap made the implementation clean while the hit rate validated the approach.

The two changes—splitting and caching—happened in the same commit because they reinforced each other. The split made the decoder easier to reason about while the caching made it faster. Together, they transformed a sprawling file into a maintainable subsystem with measurable performance characteristics.

By John Hardy, recording Debug80 project notes plus a build log.

The Debug80 extension uses VS Code webview panels to display hardware state. The TEC-1 panel shows seven-segment displays alongside the keypad with speaker activity. The TEC-1G panel adds an LCD character display with status LEDs. Both panels need JavaScript to handle message passing between the webview and the extension host. That JavaScript had accumulated inside TypeScript files as template literal strings, and it was making the codebase harder to maintain.

I counted the damage: 1453 lines in ui-panel-html-script.ts for TEC-1 plus 1413 lines in the corresponding TEC-1G file. Both files consisted almost entirely of a single exported function that returned a massive string containing mingled HTML with CSS with JavaScript. The pattern looked like this in every file:

export function getPanelScript(): string {

return `

<script>

const vscode = acquireVsCodeApi();

// ... 1,400 more lines

</script>

`;

}The problems with this approach were immediate: the editor provided no syntax highlighting or type checking for the embedded code, and autocompletion and breakpoints both failed. Every edit required careful attention to quote escaping and string interpolation boundaries. Refactoring tools could not see inside the strings. The files were technically TypeScript, but the interesting code was invisible to the toolchain.

I created a webview/ directory at the project root. For each platform, there is a dedicated subdirectory: webview/tec1/ and webview/tec1g/. Inside each platform folder, the structure is clear. The index.html file defines the layout and structure. The styles.css file handles presentation and visual details. The index.ts file manages behaviour and interactivity. To avoid duplication, a shared webview/common/styles.css holds styles used by both panels. This separation makes it easier to maintain and update each layer of the webview independently.

The HTML files use placeholder tokens that the extension replaces at runtime. Each file serves a distinct role in the rendering pipeline. One defines structure while another controls presentation; the third handles interactivity. This division of responsibilities makes the codebase easier to navigate and reason about. Instead of treating the webview as a single concern, the new approach gives each layer its own file and clear role. This makes the codebase more maintainable and easier to understand. The structure is now clear, and each file stands on its own. Every section of the webview is now clearly defined and easy to locate.

<meta

http-equiv="Content-Security-Policy"

content="default-src 'none'; style-src {{cspSource}}; script-src 'nonce-{{nonce}}';"

/>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="{{commonStyleUri}}" />

<link rel="stylesheet" href="{{styleUri}}" />

<script nonce="{{nonce}}" src="{{scriptUri}}"></script>The extension loads the template then substitutes the tokens with webview-safe URIs before serving the result. The TypeScript files compile to JavaScript through esbuild. The CSS files copy unchanged to the output directory.

I added a build script at scripts/build-webview.js that handles both platforms:

const entryPoints = [

path.join(webviewDir, "tec1", "index.ts"),

path.join(webviewDir, "tec1g", "index.ts"),

];

await esbuild.build({

entryPoints,

outdir: outDir,

outbase: webviewDir,

bundle: true,

platform: "browser",

format: "iife",

target: ["es2020"],

sourcemap: true,

});The outbase option preserves the directory structure so that webview/tec1/index.ts becomes out/webview/tec1/index.js. Static files (HTML and CSS) copy to matching locations. The extension resolver checks for compiled output first and falls back to source files during development.

The old getTec1Html function generated everything inline. The new version reads a template file and performs token substitution:

function renderTemplate(

template: string,

replacements: Record<string, string>,

): string {

return template.replace(/{{(\w+)}}/g, (match: string, key: string) => {

return replacements[key] ?? match;

});

}The function resolves paths for both compiled and source directories so that the extension works during development without a build step. When the out/webview/ directory exists, it serves compiled assets. Otherwise, it falls back to the source webview/ directory. This fallback behaviour makes iterating on webview code faster because I can edit the TypeScript directly and reload the panel without running the build.

The webview TypeScript now has proper syntax highlighting and type checking. VS Code shows errors in the problems panel. Code completion and navigation to definitions both work properly. The separation of concerns is cleaner and more explicit. HTML structure lives in HTML files, while styles live in CSS files. Behaviour lives in TypeScript files and ties the layers together. This clear separation improves maintainability and helps new contributors understand the project faster. Each section of the webview is now easier to update and debug. The responsibilities are now distributed rather than blurred, which makes the codebase easier to maintain and less error-prone.

The total line count dropped from 2,866 to around 1,800 across the new files. This reduction happened partly because I removed duplicate code between the two platforms. Proper formatting without string escaping also takes fewer lines. The remaining code is easier to read and maintain. The codebase is now more approachable for future changes.

The build adds a step to the release process, but the tradeoff is worthwhile. Development-time feedback catches errors that previously hid inside opaque strings. The webview code is now a proper citizen of the TypeScript ecosystem, no longer an awkward guest.

I should have structured the webview code this way from the start. The JavaScript-in-strings pattern emerged because I wanted to keep everything in one file during early prototyping. That convenience became a liability as the panels grew more complex. The refactoring cost was modest—a few hours of work—but it would have been cheaper to establish the pattern before the code reached 2,866 lines. This experience taught me the value of clear structure and early investment in maintainability.

The extraction pattern applies to any VS Code extension with non-trivial webview content. Template files with token substitution work alongside a TypeScript bundler and a resolver that handles both development and production paths. The structure scales to multiple webviews without duplicating the infrastructure code.

By John Hardy

The TEC-1G breaks from the TEC-1 tradition of partial address decoding. The original TEC-1 decoded only the low three bits of the port address so that port 0x00 plus port 0x08 addressed the same hardware. The TEC-1G uses full eight-bit decoding with each port having a unique address that does not mirror anywhere else in the I/O space. The Debug80 simulation inherited the TEC-1's partial decoding because I started the TEC-1G runtime by copying the TEC-1 code then modifying it. Ports were mirroring incorrectly so programs that relied on the full decoding would see wrong behaviour when they accessed ports at addresses the simulation did not recognise.

The fix required reviewing every port access in the simulation then changing the address comparisons from masked checks to exact matches. Where the code previously tested (port & 0x07) === 0x01 to detect the seven-segment display port it now tests port === 0x01 for the TEC-1G. It keeps the masked check only for the TEC-1 runtime. The change cascaded through the I/O handlers because each handler needed to know which runtime it belonged to. I extracted the port constants into platform-specific configuration objects so the handlers could reference config.SEGMENT_PORT rather than hardcoding the number. The configuration approach also made it easier to add new ports later since I just add an entry to the configuration object then write a handler rather than scattering magic numbers through the code.

The TEC-1G adds a system control register at port 0xFD that programs use to configure the memory mode alongside the serial port speed alongside other system-wide settings. Writing to this register changes the hardware behaviour immediately so the simulation needed to intercept writes then update its internal state. The memory mode bits control the shadow plus protect plus expand features I described in the first article. Writing a value with the shadow bit set enables shadowing. The simulation checks that bit when resolving memory reads plus writes. The register is write-only on the real hardware. Reading it returns undefined values so the simulation returns zero for compatibility with programs that accidentally read the port.

The system input register at port 0xFE provides read-only status information including the speaker feedback line plus the serial input state plus the memory configuration switches. The simulation exposes these values so programs can query the hardware state. The memory configuration switches determine the power-on memory mode. The simulation reads them from the platform configuration so I can test programs that expect different switch settings without modifying the runtime code. The speaker feedback line reflects the last value written to the speaker output which programs use for software timing loops. The serial input comes from the terminal emulation so when I type in the terminal panel the bits appear in this register.

The TEC-1G's expansion port includes a banking register that selects which region of a large external memory appears in the expansion window at addresses 0x8000 to 0xBFFF. Programs write a bank number to this register to page in different sections of an attached memory board. The simulation models this with a bank index that multiplies by the window size when translating addresses. Reading from 0x8000 with bank three selected actually reads from offset 0xC000 in the expansion memory array. The bank switches instantly when the register is written without any delay or interleaving. The expansion memory itself is a configurable array that defaults to sixteen kilobytes. I can override the size in the platform configuration to simulate larger or smaller expansion boards. If a program accesses an address outside the configured memory the simulation returns 0xFF which matches the behaviour of an empty bus.

The corrected port decoding means programs run correctly on the simulation even when they assume full eight-bit addressing. This includes most TEC-1G software since authors know the hardware has exact decoding. The SYSCTRL plus SYSINPUT registers let me debug programs that change memory modes at runtime. I can watch the transition from shadow mode to normal mode then verify that the addresses resolve correctly before plus after. The expansion banking support opens the door to testing programs that use external memory. While I do not have a physical expansion board to verify against the simulation follows the documented behaviour so it should work when the hardware arrives.

By John Hardy

The TEC-1G uses an HD44780-compatible LCD display that shows sixteen characters on each of its two rows. When I started the Debug80 project I implemented only enough of the controller to get text on the screen. That meant writing characters to DDRAM plus reading the busy flag. The display would show characters where the program wrote them but cursor movement was wrong while shifting did not work while custom characters were missing entirely. The incomplete simulation meant I could not debug LCD-related code effectively because the display behaved differently from the real hardware. I set out to fill in the gaps then make the simulation accurate enough to trust.

The entry mode register controls what happens after each character write. The HD44780 supports two behaviours depending on the increment/decrement bit plus the shift flag. After writing a character the address counter either increments or decrements. The display optionally shifts in the opposite direction. The implementation stores the entry mode bits then applies them after each DDRAM write. If the mode is increment with shift then writing a character advances the cursor then shifts the entire display left. This creates a scrolling effect where new text pushes old text off the screen. The challenge came in handling the wrapping since the address counter wraps from the end of DDRAM back to the beginning. The display shift is cyclic so characters that shift off one side appear on the other. Getting those details right required reading the datasheet multiple times then comparing the simulation output to captured traces from real hardware.

The display control register determines whether the display is on or off while also determining whether the cursor is visible while also determining whether the cursor blinks. I implemented all three flags so the simulation matches the visual appearance of a real LCD. The cursor appears as an underline when visible. When the user enables blinking it alternates between visible plus invisible on a timer. The blink rate matches the datasheet specification because programs sometimes rely on the timing for visual feedback. The display-off state is distinct from clearing the display since the contents remain in DDRAM then reappear when the display turns back on. I had to track the display state separately from the memory contents. The panel rendering queries that state before drawing so it can show a blank screen when the display is off.

The shift commands move either the cursor or the entire display without affecting DDRAM contents. The HD44780 uses the same command byte for both operations with a single bit distinguishing them. Cursor left shifts the address counter down while display left shifts all the characters one position to the left. The shift amount is always one position since programs build larger shifts by issuing the command multiple times so the simulation just applies the shift each time it sees the command without trying to batch them. The display shift maintains the relationship between DDRAM addresses plus display positions. If I shift the display right the character that was at the left edge wraps to the right edge. The address counter still points to the same DDRAM location even though the visible content has moved.

The CGRAM feature lets programs define custom characters by writing pixel patterns to a dedicated memory region. Each custom character occupies eight bytes corresponding to the eight rows of pixels. Each byte holds five bits for the five columns. The HD44780 supports eight custom characters stored at CGRAM addresses zero through seven. Programs display them by writing character codes zero through seven to DDRAM so the simulation intercepts those codes then renders the custom pattern instead of looking up a font glyph. The panel drawing code reads the CGRAM contents then builds a pixel grid for each custom character. The grid uses the same scaling as the built-in font so custom characters blend in visually. This makes the simulation useful for programs that define custom icons or graphics.

The completed LCD simulation means I can debug TEC-1G programs that use the display without worrying that the simulation will diverge from the hardware since scrolling text appears correctly while custom characters appear correctly while blink effects appear correctly. When a program fails to initialise the display properly the simulation shows the same wrong output the real hardware would show. This helps me identify initialisation bugs rather than blaming the simulation. The accuracy also builds confidence in the platform runtime because if the LCD simulation matches the rest of the peripheral simulation is more likely to be correct. That confidence lets me focus on my program instead of second-guessing the debugger.

By John Hardy

The original Debug80 panel was a standard webview that opened in an editor column. While that worked fine for focused debugging it fought for space whenever I needed to see both the source code plus the panel simultaneously. I would end up resizing constantly dragging the split bar back then forth as my attention shifted. The panel would steal focus when I did not want it to so the editor lost keyboard input until I clicked back. The sidebar seemed like a better home because it sits to the side of the editor by default while staying visible without demanding attention while using the familiar activity bar icon pattern that VS Code users already understand. I set out to migrate the panel from a plain webview to a WebviewView.

A WebviewView is a webview that lives in the sidebar rather than an editor column though it can also live in the bottom panel. VS Code registers them through a viewContainer contribution in the extension manifest so the first step was declaring a new activity bar container with an icon then contributing a view inside that container. The view contribution specifies a factory function that creates the webview contents. The factory receives a WebviewView instance alongside a context object so I moved the existing rendering logic into that factory. The HTML plus JavaScript remained almost unchanged since the webview API is the same whether the webview lives in an editor column or the sidebar. I had to adjust the CSS layout because the sidebar width is narrower plus fixed so I switched from a multi-column layout to a single scrollable column.

The activity bar icon gives users a persistent way to show or hide the panel. Clicking the icon reveals the sidebar with the Debug80 view selected which is the standard pattern for tools like the file explorer plus source control. I chose a simple debug-themed icon that matches the VS Code aesthetic. The icon supports a badge that shows a count so I wired it up to display the number of active breakpoints. This gives me a quick glance at the debugging state without opening the panel. The badge updates whenever breakpoints change through the webview messaging channel so the extension host does not need to poll which keeps the UI responsive even when the debugger sits paused at a breakpoint.

With the panel in the sidebar I wanted it to automatically track the active debug session. If I have multiple sessions running simultaneously the panel shows the one I am currently interacting with. The extension listens for debug session changes then posts a message to the webview when the active session changes. The webview then requests state from the new session then updates its display. The routing also handles session termination gracefully since when a session ends the panel clears its display then shows a placeholder message inviting me to start a new session. This prevents the panel from showing stale data that might confuse me if I forgot which session I was looking at.

A side effect of the sidebar placement is that the webview can persist across debug sessions which was not possible with the editor-column approach because closing the session closed the editor so the view state would reset every time. The sidebar view stays open so I added state serialization so the view remembers its scroll position alongside the collapse state of each section alongside any search or filter text. When I start a new session the view picks up where I left off. The serialization uses the webview state API rather than the extension's global state which scopes the data to the view instance plus avoids polluting the global namespace so each workspace can have its own view preferences.

The sidebar placement integrates the panel seamlessly with VS Code rather than presenting an add-on that demands attention. I can keep it visible while editing code without the constant resizing dance. The activity bar icon provides a quick toggle when I do not need the panel. The badge keeps me informed without requiring me to open anything so I know at a glance how many breakpoints I have set. The session-aware routing means I do not have to think about which session the panel is showing because it follows my focus automatically. The preserved state means I can pick up where I left off even after restarting VS Code. These changes give the debugger an integrated appearance rather than a bolted-on afterthought. I find myself leaving the panel visible all the time now because it no longer obstructs my workflow.

By John Hardy

Every time I launched a debug session the adapter would parse all the listing files then build the debug map from scratch. For a small project that took a fraction of a second but as I added more ROM sources plus extraListings entries the startup time grew noticeable. The fix was straightforward since the listing files rarely change between sessions. If I could detect when the inputs matched their previous state I could skip the parsing then reuse the previous map. The mechanism I chose was content hashing because it handles the case where someone touches a file without modifying its contents.

The caching system computes a SHA-256 hash of every input file at session start then concatenates those hashes in a deterministic order then hashes the concatenation to produce a cache key. If any input file changes the key changes then the cache misses. The adapter stores the serialized debug map alongside the cache key in a JSON file. The location defaults to the VS Code global storage directory so it persists across sessions without polluting the workspace though a configuration option allows overriding the path for users who want the cache in a project-specific location. On subsequent launches the adapter first checks whether the cache file exists then checks whether the stored key matches the computed key. If both conditions hold it deserializes the map then skips parsing entirely. This cuts startup time from seconds to milliseconds for projects with large ROM sources. Any source change automatically invalidates the cache so I never see stale data. The invalidation logic is conservative since even a whitespace change to a listing file triggers a rebuild.

I also wanted the debugger to notice when I edit a source file during a session. The adapter now registers file watchers on all the listing plus source files it loads at session start. When a watcher fires the adapter clears the in-memory map for that file then triggers a rebuild. The rebuild is incremental since the adapter reparses only the affected file while the rest of the map remains intact which keeps the disruption minimal. The debugger continues running during the rebuild so I do not lose my place. This matters most when I am iterating on a bug in the ROM source because I can edit the listing file then save it then immediately see the updated source lines in the editor without restarting the session.

A small but persistent annoyance was that starting a debug session required manually opening the source file before I could set breakpoints. I added an option called openSourcesOnSessionStart that takes a list of file patterns. When a session starts the adapter expands those patterns against the source map then opens matching files in the editor. The typical configuration opens the main program file plus any ROM sources I frequently debug. The files open in the background so they are ready when I need them but do not steal focus from the active editor. The patterns support globs so I can specify *.asm to open everything. I can specify /mon-3/ to open only the MON-3 sources. The pattern matching uses the same library the rest of the codebase uses for path resolution which keeps behaviour consistent.

The memory panel started as two separate webviews because the TEC-1 plus TEC-1G platforms had different memory layouts. I wanted each to show only the relevant regions but maintaining two implementations doubled the work whenever I changed the panel styling. Adding a feature meant doing the work twice. I merged them into a single panel that queries the adapter for the platform's memory map at session start. The unified panel renders a list of regions where each region gets a collapsible section with a hex dump. The section header shows the region name alongside its address range which makes it easy to scan for the region I want. The adapter provides the memory map within the platform configuration so adding a new platform with a different layout does not require changing the panel code since the panel just iterates the regions it receives.

The caching change makes launching a session feel instant. This matters because I often stop then restart sessions when I am exploring a bug then want to reset the CPU state. Waiting for the map to rebuild was interrupting my flow. The auto-open feature means the source is ready when I need it so I can set a breakpoint in the first few seconds without hunting for the file. The consolidated memory panel reduces maintenance burden while giving me a clearer view of the address space. These are small quality-of-life improvements but they compound over a long debugging session. The debugger now feels polished rather than rough like a tool I enjoy using rather than one I tolerate.

By John Hardy

When I step through a TEC-1 program the interesting work often happens at the boundary where my code calls into the monitor ROM then the ROM calls back into my routines. The trouble was that Debug80 only knew about the source files I assembled for the current session. This meant the ROM was a black box since I could see it executing in the disassembly view but I could not see the original source lines. I could not set breakpoints by label either. That gap made it hard to understand what the ROM was doing when my program misbehaved so the fix required two changes to the debugger architecture. The debugger needed a way to load additional listing files that live outside the project. It also needed to build source maps from those listings so that stepping plus breakpoints work the same way they do in user code. The result is a new extraListings configuration option that accepts a list of paths to .lst files. When a debug session starts the adapter loads each listing then parses it then merges the resulting segments into the main source map.

The configuration lives in debug80.json alongside the other platform settings. A typical TEC-1 setup now includes the extra listings array pointing to the ROM listing file. The path resolves relative to the debug80.json base directory though absolute paths also work for users who want to reference listings from a central location. If a listing file is missing the adapter logs a warning to the Debug Console then continues without it. This keeps the session usable even when the ROM source is unavailable. This graceful degradation means that users can share project configurations without requiring everyone to have the same ROM sources installed. The adapter loads each listing at session start then parses the contents line by line building a source map that the debugger uses to correlate addresses with source lines throughout the session.

A listing file contains the assembled output alongside the original source lines. The format varies by assembler but the essential structure is an address column followed by a hex dump of the generated bytes followed by the source text. The adapter parses each line then extracts address ranges for every instruction. Those ranges become segments in the source map where each line with a valid address becomes a segment recording the start address plus the byte count plus the line number. When the CPU hits an address in that range the debugger can now jump to the correct line in the listing file to show the original assembly code alongside the current register state. The parsing logic handles the common listing formats including asm80 plus tasm plus zmac output. The adapter detects the format automatically by examining the first few lines of the file which means users do not need to specify the assembler they used.

Listing files work well when they exist but sometimes I only have the original assembly source. I wanted the debugger to handle that case too. If a listing file sits next to a .source.asm file with the same base name the adapter compiles the source using asm80 then builds the mapping from the compiler output. If it sits next to a plain .asm file that also works. The compilation happens at session start when the adapter calls asm80 directly via its JavaScript API using a file resolver hook that lets asm80 resolve include files relative to the source directory. The compile result contains a list of lines with addresses plus byte counts plus a symbol table. The adapter walks both structures then builds segments plus anchors for the source map. This means I can drop a ROM source file next to the listing then the debugger will pick it up automatically. I can set breakpoints by clicking in the source margin while the stack trace shows the original labels instead of raw addresses.

With multiple ROM sources loaded I needed a way to open them during a session. The debugger now registers a command called debug80.openRomSource that queries the adapter for the list of loaded ROM sources then presents them in a quick pick menu. Selecting an entry opens the file in the editor. The command distinguishes between listing files plus source files. If both exist for the same ROM the picker shows both options so I can choose the listing when I want to see the hex dump. I can choose the source when I want to read the assembly without the noise. The picker also shows the file path plus the address range the source covers. This helps me find the right file quickly when working with multiple ROM modules that each have their own source files.

The TEC-1G adds another layer of complexity because its memory controller can shadow the ROM region at 0x0000–0x07FF with RAM at 0xC000–0xC7FF. With shadow mode active the CPU sees the high RAM contents at the low addresses. This is how the TEC-1G boots since the ROM lives at 0xC000 but the CPU starts execution at 0x0000 because the shadow activates at power-on. The debugger needed to understand this aliasing because when I set a breakpoint at a ROM label the label resolves to an address like 0xC100. With shadow mode active the CPU executes that code at 0x0100 so the breakpoint would never fire because the addresses did not match. I fixed this by teaching the breakpoint checker to consider shadow aliases. When the CPU stops the adapter checks both the raw PC plus its shadow alias against the breakpoint set. The same logic applies to source lookup so if the PC is in the shadowed region the adapter tries the shadow alias when resolving the source file.

This change also required updating the TEC-1G runtime to enable shadow mode at power-on because the previous behaviour started with shadow disabled. This meant the ROM had to explicitly enable it before execution could begin. That was incorrect since the real hardware boots with shadow active so the CPU can fetch from ROM at address zero.

I can now step through the TEC-1 monitor ROM the same way I step through my own code. When my program calls GETKEY I can follow execution into the ROM then watch it scan the keypad. When a subroutine misbehaves I can set a breakpoint inside the ROM then inspect the state when it fires. The source map merging means that the debugger treats ROM code plus user code as a unified address space. The stack trace shows labels from both. The disassembly view annotates ROM addresses with their source lines. The memory panel can jump to ROM symbols. This is the debugging experience I wanted from the start. The ROM is no longer a black box but just another module in the program visible plus inspectable like everything else.

By John Hardy

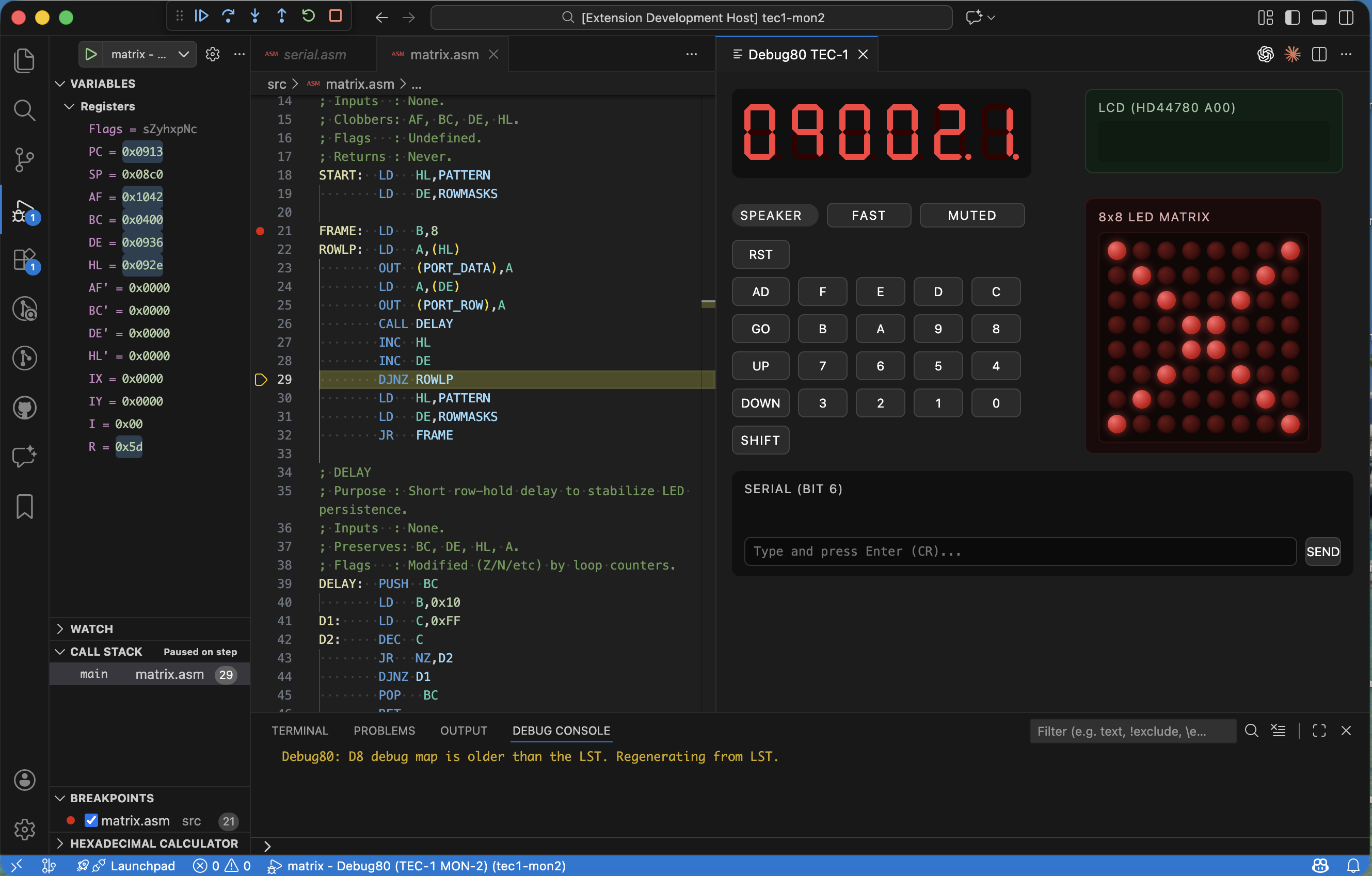

The TEC-1 was always a teaching machine that shipped with 2K of ROM alongside 2K of RAM alongside a hex keypad that taught you to think in machine code. The TEC-1G keeps that spirit but expands the hardware significantly by offering 32K of RAM alongside a 16K monitor ROM alongside an LCD character display alongside memory banking features that let programs grow beyond the original constraints. These are not incremental changes because they reshape how programs are written alongside how the debugger must behave. I could have stretched the existing TEC-1 platform to cover the TEC-1G but that would have buried the differences in conditionals alongside special cases. Instead I added a dedicated tec1g platform to Debug80 with its own memory map alongside its own I/O port handlers alongside its own panel UI. The two platforms share some low-level code but they present themselves as distinct machines with their own identity so this separation makes it easier to maintain accurate emulation for both systems without one platform's quirks affecting the other.

The TEC-1 has a simple layout with ROM at 0x0000–0x07FF alongside RAM at 0x0800–0x0FFF. Most programs fit comfortably in a small region near the bottom of memory. The TEC-1G uses the full 64K address space with zones that serve different purposes. Understanding this layout is essential for proper platform configuration. The shadow region at 0x0000–0x07FF is RAM that mirrors ROM when shadow mode is active. Free RAM including monitor workspace occupies 0x0800–0x3FFF while protect-capable user RAM lives at 0x4000–0x7FFF. The expansion window at 0x8000–0xBFFF shows 16K of a 32K banked device. The MON-3 monitor ROM occupies 0xC000–0xFFFF at the top of memory rather than the bottom which is the opposite of the TEC-1 placement.

Programs start at 0x4000 instead of 0x0800. The first time I tried to load a TEC-1 program on the TEC-1G platform it landed in the wrong place. The display showed garbage because the memory map was not a detail I could ignore. The platform configuration reflects this layout precisely with regions defined for ROM zones alongside RAM zones. An appStart of 16384 (0x4000) tells Debug80 where user programs begin while an entry of 0 means the CPU starts at address zero while the shadow mechanism makes that address show ROM contents at boot time. This configuration leads to the three memory modes that make the TEC-1G distinctive. Getting them right was essential for accurate emulation.

The TEC-1G has three memory modes controlled by a system control port at 0xFF where each mode serves a distinct purpose in the machine's operation. Grasping these modes is essential for writing programs that work correctly on the hardware. Shadow mirrors the ROM at 0xC000 into the low 2K at 0x0000–0x07FF which is how the machine boots because the CPU fetches from address zero but sees the ROM contents. Shadow mode also exists for compatibility with programs that expect to run from low memory allowing the same code to work on both machines without modification. Protect makes the user RAM region at 0x4000–0x7FFF read-only which serves as a safety rail because when you are typing in a program byte by byte a stray store instruction can erase your work. Protect mode stops that from happening since it is a workflow feature rather than a security feature.

Expand selects which half of the 32K expansion device appears in the 0x8000–0xBFFF window. The TEC-1G expansion socket can hold 32K but only 16K is visible at a time. Toggling the expand bit swaps the visible half to give programs access to more memory than the address space would otherwise allow. The runtime tracks these modes in state variables then enforces them during memory access. The adapter checks shadowEnabled alongside protectEnabled alongside expandEnabled flags on every read operation along with every write operation. When the adapter handles a memory write it checks both the protect flag alongside the address range. A write to 0x5000 succeeds when protect is off but silently fails when protect is on which matches the hardware behaviour exactly.

The original implementation started with shadow disabled but that was wrong because the real TEC-1G boots with shadow active so the CPU can fetch the ROM reset vector from address zero. The ROM then initialises the system then optionally disables shadow mode before jumping to user code. I fixed setting by setting shadowEnabled: true at power-on alongside on reset which ensures the emulator behaves the same way as the real hardware from the first instruction fetch. The reset handler also needed updating because when the user resets the machine the emulator must restore shadow mode so the boot sequence works correctly. Failing to do this would cause programs to crash unpredictably after a reset.

The TEC-1G ships with MON-3 which is a 16K monitor ROM written by Brian Chiha that represents a significant upgrade from the original MON-1. MON-3 includes a menu system navigated by Plus/Minus plus GO alongside Intel HEX loading over serial alongside block copy alongside backup utilities alongside memory export in multiple formats alongside a built-in disassembler alongside Tiny BASIC alongside real-time clock support alongside graphical LCD library routines. The debug80-tec1g repository packages MON-3 with its source alongside listing files including the binary ROM image alongside the Intel HEX format alongside the assembler listing alongside the original source code alongside included modules for Tiny BASIC plus LCD routines plus disassembly plus the real-time clock plus sound. The extraListings configuration points at mon-3.lst so the debugger can step through monitor code with full source context. When execution enters a ROM routine the source view shows the original assembly instead of raw disassembly.

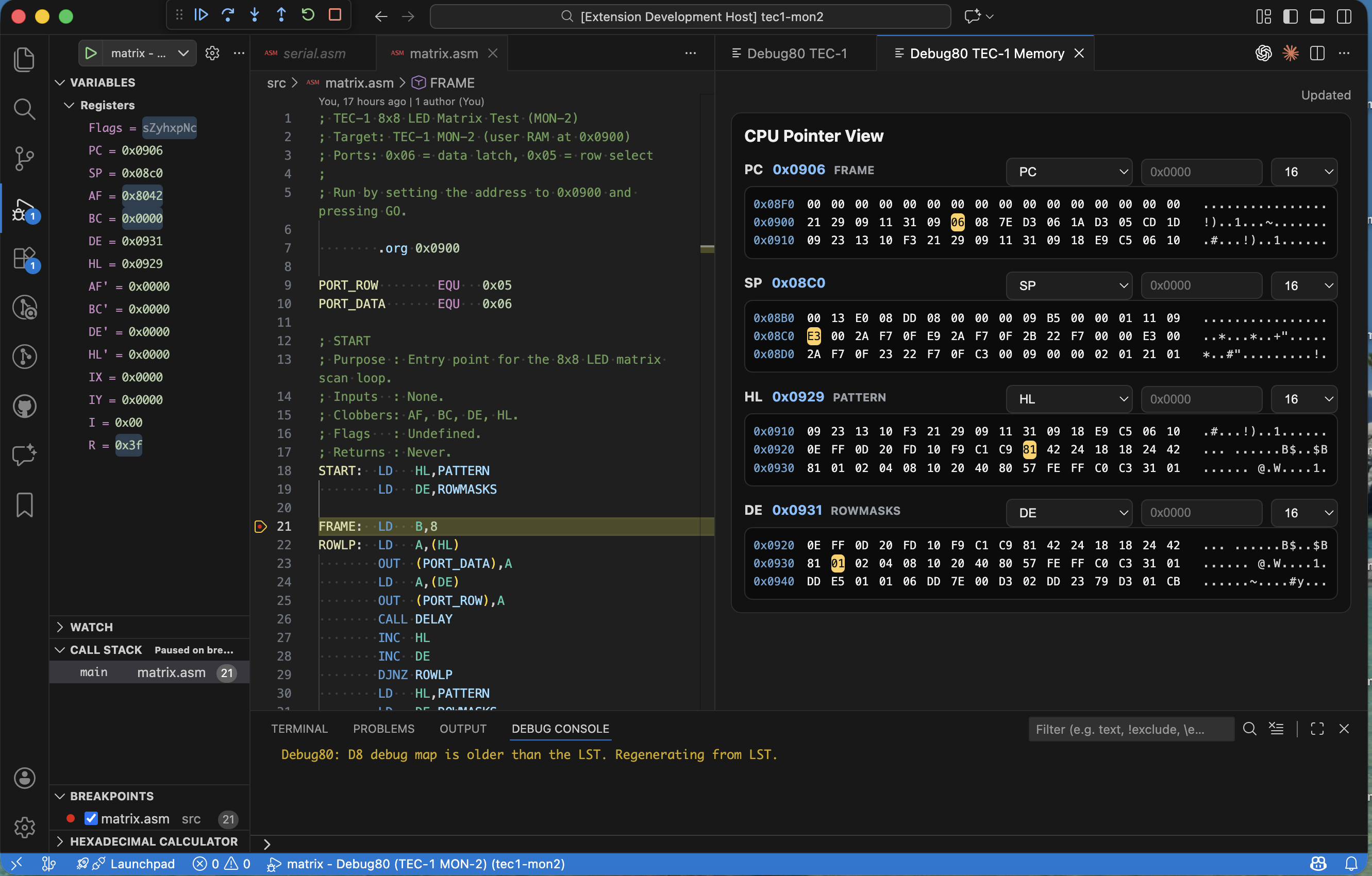

Debug80 itself stays generic because the platform-specific details live in separate repositories that users clone alongside their projects which keeps the core debugger clean while allowing unlimited platform variations. The debug80-tec1 repository contains TEC-1 machine setups including tec1-mon1/ for MON-1 configuration with RAM at 0x0800 plus tec1-mon2/ for MON-2 configuration with RAM at 0x0900 plus sample programs demonstrating serial communication plus matrix keyboard scanning. The debug80-tec1g repository contains TEC-1G machine setups including tec1g-mon1/ for MON-1B compatibility mode plus tec1g-mon3/ for the full MON-3 configuration with RAM at 0x4000 plus sample programs demonstrating LCD control plus other TEC-1G-specific features.

Each machine folder has a .vscode/debug80.json that configures the platform alongside ROM paths alongside extra listings. A developer can open one of these folders in VS Code then immediately start debugging without writing configuration from scratch. The separation means that adding a new machine does not require changes to Debug80 itself. A new TEC-1 variant can live in its own repository with its own ROMs alongside configuration templates while a completely different Z80 system can do the same. The community can share platform configurations without needing to modify the core extension.

The TEC-1G panel extends the TEC-1 panel with LCD support. It shows the seven-segment display with address registers plus data registers alongside a character LCD that renders the HD44780 display buffer. The panel also displays the current mode indicators for Shadow plus Protect plus Expand so I can see at a glance which memory features are active. The LCD rendering uses the same device model I described in an earlier article. Writes to the LCD command port plus data port update an internal buffer. The panel paints the buffer as a grid of glyphs that update on each cycle. The TEC-1G panel queries buffer on each update cycle then refreshes the display to show exactly what a real LCD would show which makes it easy to develop plus debug LCD-based applications without needing the physical hardware.

I can now debug TEC-1G programs with the same tools I use for TEC-1 programs but without pretending the machines are identical. The memory map resolves correctly so that ROM lives at the right address while protect mode works as expected while shadow mode boots the machine properly. When I step through a MON-3 menu handler the debugger shows the original source. Setting a breakpoint in a ROM routine works correctly because the breakpoint fires even though the code runs in shadowed memory. The platform abstraction handles the address aliasing so I do not have to think about it. The TEC-1G is a more capable machine than the TEC-1 so the debugger now reflects that because it is not a compatibility hack but rather a first-class platform with its own identity plus configuration that respects the hardware's unique characteristics.

The TEC-1 work started inside the debug80 repo because I needed to move fast. That was the right choice for the first experiments, but it meant the core extension began to carry program bundles and ROM assets. It also had a loader UI that belonged to the platform, not the core debugger. The repo was beginning to feel like a platform pack instead of a core tool.

I removed the TEC-1 program loader and the programs/tec1 tree from the extension. That cut out the debug80/tec1LoadProgram request in the adapter. It also removed the program picker from the TEC-1 panel. The bundled serial and matrix demos went with it. The core debugger now focuses on the adapter. It still provides the runtime and UI surfaces, but it no longer owns machine content or program curation.

That removal forced the line between tool and platform. The answer was a new repo named debug80-tec1. It holds the machine setups and their assets. The structure is intentionally small so each machine reads like a runnable workspace. It has a MON-1 folder and a MON-2 folder. A shared ROM directory sits beside them. Each machine folder has a .vscode/debug80.json with named targets and a default target so the setup can be run immediately.

Both ROMs run on the same TEC-1 hardware. The difference is the memory map, not the machine itself. MON-1 user programs start at 0x0800. MON-2 user programs start at 0x0900 because MON-2 keeps variables and the stack in the 0x0800–0x08FF region. Each target declares ROM and RAM regions. It also declares the application start address and the ROM hex file to preload. The serial and matrix demos live alongside those targets in src/, which makes each machine folder a runnable workspace.

I also started tracking ROM binaries in git. The mon-1b.bin and mon-2.bin files sit next to their hex and source representations. That keeps provenance visible and makes the repo self-contained. It matters when the goal is a platform pack that works on any machine without extra downloads.

The split is more than a cleanup. It makes debug80 easier to maintain because the core stays focused on the debugger. The TEC-1 platform can evolve on its own cadence. It also sets a pattern for future platforms so they can keep ROMs and targets together in one place. Test programs can live beside them without bloating the core extension.

I wanted a place where I could read the machine state directly. Registers are fine, but they do not show what the bytes around them look like. When I was stepping through programs I kept jumping between the listing and the hex view in my head. That is when I decided to build a dedicated memory panel for the TEC-1.

The first step was a new command, debug80.openTec1Memory. I built a webview that could sit beside the main TEC-1 panel. The adapter gained a custom request named debug80/tec1MemorySnapshot. It reads the current register set and chooses a centre address. It then returns a window of bytes around that address. The adapter aligns the window to the row size so the panel does not jitter as the pointer moves. A focus index marks the exact byte under the pointer, which lets the view highlight the address that triggered the snapshot.

The first version shipped with three views, with PC and SP fixed in place. The third view followed HL, with an optional absolute address override for quick jumps. The panel refreshes on a short timer so it stays in step during stepping and short runs. I did not want to force another button press every time I hit Step.

As soon as I started using it, the limits became obvious. A single view is not enough when the program counter and stack pointer move while a data pointer moves too. I rewired the snapshot payload to accept a list of views instead of a single view. Each view entry carries its own id and view mode. The window size is set per view. The adapter now produces a response that mirrors the list so the panel can update all views in one round trip.

That change made the panel a four-pane dashboard. PC and SP now sit beside HL and DE, each with its own window length. I kept the row size consistent and the alignment rules identical so the panes stay visually comparable. This is a small detail, but it matters when you are scanning two panes and trying to align addresses by eye.

The last piece was symbols, because I wanted to see where I was without opening the listing. The adapter now builds a symbol index when a session starts. If the mapping already has anchors, it uses them. If not, it parses the listing for lines like “DEFINED AT LINE”. It extracts the symbol name and address, then records the file for each line. I then sort those anchors and filter them against valid mapping ranges so I do not label bytes that fall outside the assembled segments.

The snapshot response now returns two symbol payloads. Each view includes the nearest symbol plus the offset from that symbol. The panel also receives the full symbol list, which it uses to add a symbols group to each view selector. When I choose a symbol, the panel resolves it to an absolute address and updates the view.